In 1966 rock 'n roll got it's first real taste of the blending of folk, country, blues and rock, through the prism of a new band out of Los Angeles called Buffalo Springfield. Initially it was Stephen Stills' band, with his former folkie group-mate Richie Furay harmonizing, an R & B drummer named Dewey Martin, and two unknown Canadians, Bruce Palmer on bass and this mysterious character who either turned his back to or never seemed to look at the camera, Neil Young.

They produced three LP's and one of the most iconic and enduring folk-rock singles of the 60's, Stills' "For What It's Worth". They tore it up with perhaps their most powerful rock 'n roll track, Neil's "Mr. Soul", and blended nearly every musical style known to man in tracks like "Nowadays Clancy Can't Even Sing" and "Bluebird". The “music business” at the time still operated under the presumption that every act signed to a major label would produce hit singles for AM radio. For a band as progressive and driven creatively as Buffalo Springfield, with the triumvirate of musical savants in Stills, Furay and Young, this formula-driven expectation was anathema.

The age of the album as an entity unto itself making it onto radio had yet to be truly born. Young's natural bent toward doing his own thing despite commitments to the group led to endless conflicts, and the group's third album "Last Time Around" found the various members recording separately, seldom any two of them in the studio at the same time, submitting finished recordings that in the case of Neil Young's material didn't even include any of the other band members. By 1968, Buffalo Springfield was no more. Their influence however, was immediate, and was certainly felt even among their contemporaries in Los Angeles, among them, The Byrds.

Folkies turned electric rockers through the influence of the Beatles, The Byrds were founded by former Chad Mitchell Trio guitarist and banjo player Jim (later Roger) McGuinn. The group included established folkies Gene Clark and David Crosby, aspiring coffee-house & country picker Chris Hillman who gave up his guitar and mandolin to pick up bass guitar, and Michael Clarke looked like a musician so he became the drummer, much as Skip Spence had done with the original Jefferson Airplane up in San Francisco.

Gene Clark gave up his guitar on stage to literally become their "Mr. Tambourine Man", a status that eventually wore thin, and Clark left in 1966 after just two albums. The third album "Fifth Dimension" showcased more of Crosby and McGuinn's experimental sides in tracks like "2-4-2 Foxtrot", with a decidedly heavier sound that included Gene Clark's final contribution "Eight Miles High" and perhaps the first anti-nuke song, "I Come And Stand At Every Door".

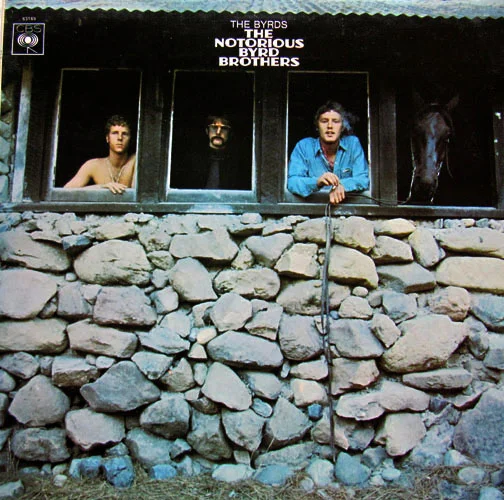

Their next was the landmark "Younger Than Yesterday", a classic featuring more country influence from Chris Hillman, notably the brilliant "Time Between", considered by many to be the first true 'country-rock' track. By 1967 Byrds' internal affairs had come to a boil between McGuinn and Crosby, brought to a head at the Monterey Pop Festival when Crosby went on a political rant which didn't amuse the group. Crosby then filled in for no-show Neil Young during Buffalo Springfield's set, a mix 'n match becoming common in San Francisco and LA, but not appreciated by McGuinn. The next Byrds' single "Lady Friend", was the last for Crosby. The group photo already taken for the next album of the four members peering out of barn windows, was altered, originally planned with the rear end of a horse replacing Crosby's smiling face. The front end of the horse thankfully ended up on the released version, but Crosby was a Byrd no more, and 1968 found him at loose ends.

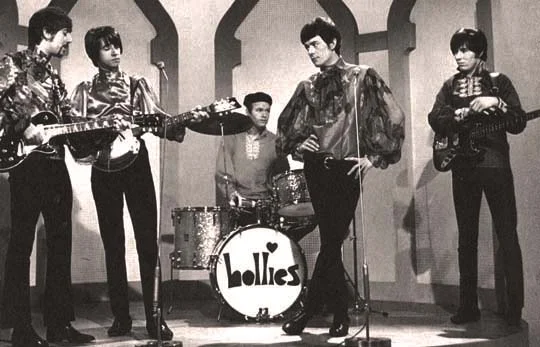

On the other side of the ocean a hit-machine known as The Hollies were having their own problems. With huge global chart toppers under their belts like "Bus Stop", "Look Through Any Window", "Here I Go Again", "On A Carousel," etc, The Hollies were among the very few English bands who survived the “British Invasion”. While most of their contemporaries fell through the cracks after getting one or two singles onto the American charts, the Hollies had endured.

Powered by the glass-shattering 12-string and backing vocals of Tony Hicks, the glorious lead vocals of Allan Clarke, and incredible high-flying harmonies of Graham Nash, The Hollies were respected and respectable, but by 1967 beginning to have internal conflicts between continuing to concentrate on recording hits as opposed to being taken seriously as artists.

"Carrie Anne" confirmed their staying power as a singles band, but a proposed project featuring the Hollies covering an album's worth of Bob Dylan material left Graham Nash running for the exit. He had no interest in becoming a tribute band, nor seeing the Hollies evolve into The Byrds for that matter, a band whose connection with Dylan's material was firmly embedded. "King Midas In Reverse" and "Jennifer Eccles" became Nash's final singles with the Hollies, as the band went ahead with the Dylan album without him. In 1968 Graham Nash was in California without a band or a plan.

And then it was 1969.

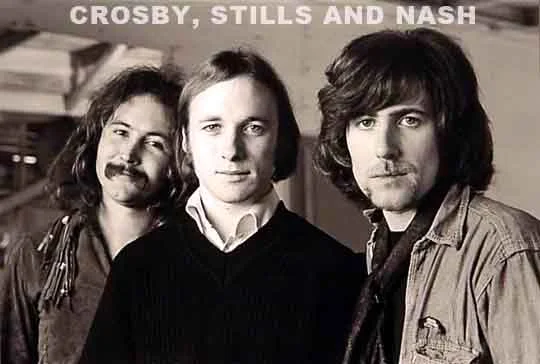

Ads were running in Rolling Stone and other music/fan magazines about an upcoming festival dubbed the “Woodstock Music And Arts Fair”. Blind Faith became the first so-called "super-group", from the remnants of the true first super-group, Cream. Jimi Hendrix had done away with the Experience. Jim Morrison was busted in Miami. Janis Joplin had gone solo. Rumours were that David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Graham Nash were putting together a band. Many of us wondered how on earth such a line-up could possibly jell, given the distinct and apparent contradictory vocal sound and style possessed by each, not to mention their respective reputations as personalities, Crosby in particular, who had been kicked out of the Byrds. What would they call the band? Who else would be in it? What on earth would this sound like?

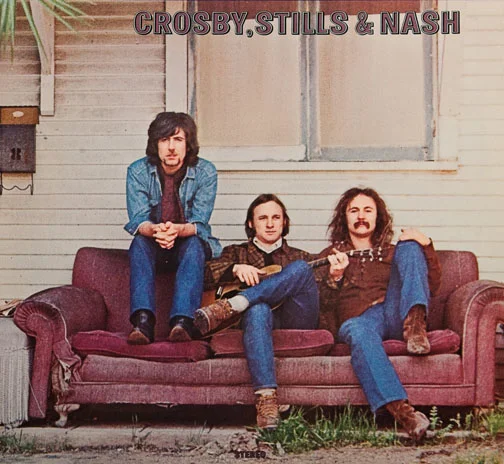

With the release of "Crosby, Stills & Nash", all questions were answered. Crosby's sometimes meandering harmonies were a perfect counterpoint to the angelic Nash, both grounded by the earthy and swirling grit and easy falsetto of Stills. It was strange, it was ethereal, it was unexpected, and it worked. And they had the unmatched audacity to name the band after themselves, a simple act that made it possible for them to tour together or separately until the end of time, as they chose.

August, 1969. Woodstock. "This is our second gig, man" "It's the second time we've ever played in front of people." By then they had, not surprisingly, been joined by the mercurial Neil Young, adding a fourth letter, a fourth name to come and go as he wished, which was in truth the way he wanted it to begin with. CSN could become CN, CSNY, SY, S, Y, N, C, and they did of course, however they might prefer to appear on any given day for the rest of their years.

The iconic recordings began to pile up. "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes", "Wooden Ships", "Carry On", "Helplessly Hoping", "Teach Your Children", "Ohio", "Our House", "Long Time Gone", "Guinnivere", "Find The Cost Of Freedom", "Southern Cross"... Their solo work could easily be incorporated into any set list. "Love The One You're With", "Chicago", "Southern Man", "Almost Cut My Hair", not to mention the always fitting "For What It's Worth", a list as long as your arm, and still growing.

Years went by. I finally saw Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young on the final show of their 2000 tour. Naturally, they were brilliant. Neil still in his ripped up blue jeans and t-shirt power-chording his way through must-hear material, Crosby, Stills & Nash harmonizing impeccably over acoustic instruments, a career spanning set of two hours that could have been, should have been ten.

In 2010 Neil called together the remaining original members of Buffalo Springfield to play that year's Bridge School benefit show. Thus Stills, Furay and Young stood on the same stage together again for the first time since 1968. As in 1969 with CSN, rumours then flew about a Buffalo Springfield reunion tour. In 2011 six California shows were announced, two each in Oakland, Los Angeles, and Santa Barbara. A 7th show doing a set at Bonnarroo Festival in Tennessee was added. I went on line and bought first or second row seats for all 6 California shows, flew to California, rented a car, and proceeded to follow Buffalo Springfield from show to show.

In a nutshell, the first show, at the Fox Theater in Oakland was probably the best. The band seemed genuinely taken aback by the reaction when they walked on stage, a roar equal to Beatlemania in 1964, although a bit more”'mature” sounding. The audience stood for their entrance and only sat down once, during Richie Furay's gorgeous "Sad Memory". In his famous fringed-leather jacket, Neil introduced themselves as "We're Buffalo Springfield, we're from the past".

The band was a bit rough around the edges, like any great garage band might be, but the music and energy ruled the day. Richie Furay, with his voice 100% intact, is as much a Buffalo Springfield icon as either of the other two in that setting, and the moment he opened his mouth to sing the first phrases of the show opener "On The Way Home" the crowd went even more wild.

Stills and Young got into a nose-to-nose jam during "Bluebird" and the only negative was that they didn't play everything they had ever recorded. Over the next five shows in my view it became progressively more of a Neil Young driven set as Stills seemed to pull back, despite Neil continually going to Stills' side of the stage trying to generate a jam.

Stills was apparently having some health issues at the time, wore a wrist brace to play piano on at least one show, and appeared to be having some forearm or carpal tunnel problems at times. He seemed somehow uncomfortable, but the show must go on.

After idolizing them in the 60's, to me they could just as well have come out and sat on stools with acoustic guitars, played some songs and told stories, the response would have been the same. On the whole it was fabulous to witness the reunion under any circumstances, and all three of them were very gracious in acknowledging the audiences who were universally ecstatic. All shows ended with Neil's "Rockin' In the Free World". Despite an interview during this run of shows with Richie Furay and Stephen Stills, during which Richie suggested there would be a 30-city tour in the fall, once again the Buffalo Springfield story came to a mysterious halt, with Bonnarroo the last show. Once again Stills and Young parted ways and Richie went back to Colorado. That was that.

Fast forward to March 12, 2014.

EPILOGUE: I'll leave it to other writers to review the Crosby, Stills & Nash show in Peoria. For my money, it was thrilling and three hours of joy. Once again, the only negative was that they didn't play everything they have ever recorded. Concerns about Crosby's health were put to rest. To those like myself who haven't seen him in a long time, he appeared to have lost weight but in a good way. Along with Keith Richards, David Crosby may be the man voted least likely to have survived beyond the 1980's. Yet at 72 he looked great, and from the first song he sounded great, played great. His humour and demeanor are fully intact and his aura is strangely “down to earth” yet that of a living legend. In true Crosby form, a walking dichotomy in terms.

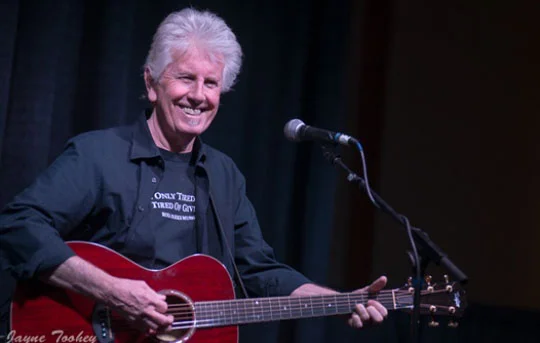

Graham Nash is a joy to behold. Somehow still the glue that so easily holds it all together, his commentary and rapport with the audience a highlight of the proceedings, and also at 72 his stage presence and performance level thoroughly undiminished by time. If he were a bottle of wine, the combined worth of everyone in the audience could not afford it.

And then there was Stephen Stills. The man I was most concerned with and about, after seeing Buffalo Springfield from the front row for those six shows in 2011. All fears, all concerns put to rest. This was the Stephen Stills I idolized in 1966. This was the guitarist I most wanted to see kick everybody's ass. I saw Cream in 1968, and their reunion in 2005. I saw Blind Faith and Clapton solo numerous times. But it has always been Stills' guitar that drew me to Buffalo Springfield, and that powered those fabulous CSN recordings. It is the interplay between Stills and Young that blazed a trail as deep as the Grand Canyon in my young and now old musician's mush brain on so many recordings, and on March 12 Stephen Stills kicked everybody's ass including mine and I am grateful for that.

His voice isn't that of his 22 year old self, but it is his, and on this night he was going for it. Iconic vocal passages were intact. His sense of humour and way with words was on full display during an incredible version of "Treetop Flyer", a rarity only die-hard fans would know. He played furiously and then gently, aggressively and then with finesse, electric, acoustic, the white Gretsch, that well-worn Strat, he was serious and he was joyous, he played catch-me-if-you-can with an errant spotlight operator who seemed to have trouble following him as he strode the stage during seering solos that had the crowd in an uproar.

He laughed and joked. In short, it was clear to all—Stephen Stills was having fun. I want to see this man have fun. It's important. I want to hear David Crosby, with a new stint in his heart, with his voice and spitfire humour intact, having fun. I want to see Graham Nash, who has endured so much worrying over the well being of his friends, and cataloging all of their work while still creating such a wealth of joyful music of his own, having fun.

I left the Civic Center feeling like a great weight had been lifted off my chest. They had fun. We had fun. Crosby and Stills are both in good shape and spirit. We should all look and sound as great as Graham Nash does at 72. It was worth every penny and more, we can only pray that there are many years left of this story.